. Krakatoa’s Really, Really Big Bang

. Krakatoa’s Really, Really Big BangThe terrible tsunami that devastated Indonesia in December 2004 wasn’t the first time nature had vented its fury on the South East Asian nation. At 10:02 a.m. on August 27, 1883, the volcano on the island of Krakatoa [wiki], in the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra, erupted. More accurately, it exploded. The detonation threw smoke and ash 17 miles in the air.

In fact, the ferocity of the burst echoed so loudly that the sound of the explosion was heard on Rodriguez Island, nearly 3,000 miles away (imagine being in New York and hearing a boom from San Francisco!). The pressure wave caused barometers to twitch as far away as London seven times as the shock bounded and rebounded around the globe.

But the eruption itself wasn’t the worst of it. The explosion sent tsunami waves over 100 feet high toward Java and Sumatra. Ships were carried a mile and a half inland and dumped in the jungle. The disruption was so great, the tide actually rose several inches in New York.

In all, more than 36,000 people were killed by the tsunami, and most of the nearby coasts of both islands were laid waste. As for Krakatoa, the island blew itself out of existence. It reemerged years later, the result of continued volcanic activity in this turbulent part of the Pacific “Ring of Fire.”

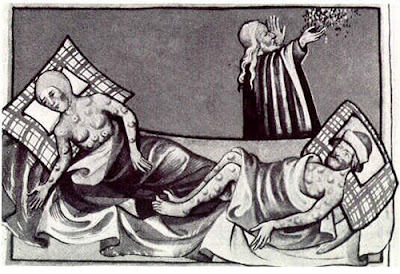

“Bring Out Your Dead!” The Black Death

“Bring Out Your Dead!” The Black DeathBetween 1347 and 1351, a plague raged through Europe. Arriving in Messina, Sicily, on a Black Sea merchant ship, the disease was initially thought of as solely an animal sickness – like bird flu or mad cow disease. But somehow fleas managed to transmit the condition from rats to people.

Called the Black Death [wiki] because of the dark spots that appeared on victims’ skin, the pandemic wasn’t just the bubonic plague. In fact, the vicious strain was actually a lethal combination of four variations of plague: bubonic (causing buboes, or inflammations of the lymph nodes), enteric (intestinal), septicemic (an infection of the blood), and pneumonic (filling the lungs with fluid). Quadruple yuck.

Even worse, the Black Death worked fast. People who were perfectly healthy at midday were dead by sunset. And the staggering death toll reflects it. An estimated 12 million people in Asia and 25 million in Europe (or one-third of Europe’s population) were wiped out.

An indiscriminate killer, the disease destroyed rich and poor alike, though only one reigning monarch is known to have died: King Alfonse XI of Castile, who refused to abandon his troops when plague struck his army.

Russia Dodges a Bullet from Space: The Tunguska Blast

Russia Dodges a Bullet from Space: The Tunguska BlastAt 7:17 a.m. on June 30, 1908, a 15-megaton explosion (more than 1,000 times that at Hiroshima) flattened a massive part of the Tunguska region of Siberia. The devastated area was 57 miles across, and the explosion shattered windows 400 miles away.

A real investigation of the event wasn’t undertaken until 1927. But that’s not the weird part. The strangest fact about the incident is that there was no impact crater. An entire forest flattened, but there was no hole, meaning the object had exploded in the air. Scientists now believe that the object was an asteroid or extinct stony comet; the pressure of its descent simply blew it apart before it hit the ground.

But the mysterious nature of the event has lead to a whole literature of ludicrous theories, blaming the blast on everything form a black hole passing through earth to a chunk of antimatter to an exploding UFO to – we love this one – an energy death ray built by Nikola Tesla and test-fired form the Wardenclyffe Tower on Long Island. Whatever they believe, scientists have shuddered and thanked their lucky stars, contemplating what might have happened had the object decided to explode over, say Central Park. Due to the remoteness of Tunguska, not a single person was killed by the blast.

The Day the Little Conemaugh Got Much Bigger

The Day the Little Conemaugh Got Much BiggerLake Conemough lies 14 miles up the Little Conemaugh River from the town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. On May 31, 1889, the dam that held back the lake waters burst after two days of torrential rain.

The results were devastating. A wall of water 60 feet high, moving at 40 mph, crashed down on the unsuspecting people of Johnstown and the water and debris it carried all but flattened the entire town. In an utterly tragic twist, the town was downstream from a wire factory that was also flattened by the water. Many townspeople caught in the deluge got so entangled in barbed wire that they couldn’t escape. In the end, 2,209 people were killed, including 99 entire families.

But Mother Nature was not wholly to blame for the tragedy. The Lake Conemough Dam was the property of the South Fork Fishing and Forestry Club, which had turned the area into a mountain retreat for the wealthy. However, the club had neglected proper maintenance on the dam. Despite its culpability, though, it was never held legally responsible.

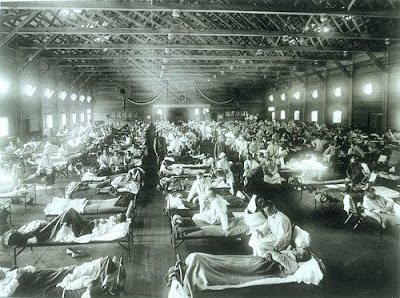

From the People Who Brought You World War I: The Flu

From the People Who Brought You World War I: The FluJust as the Great War was ending and the world looked like it might finally get back to normal, the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 struck. The pandemic most likely originated in China, but its huge and devastating impact on Spain’s population earned it the name “Spanish flu” while the French called it “La Grippe.” Even such luminaries as President Woodrow Wilson caught the bug, in his case while attending the Versailles Peace Conference. In the end, one-fifth of the world’s population would become infected, and more people would die – some estimates are as high as 40 million – than had during four years of fighting in the First World War. Ironically, the war can be held party responsible not only for spreading the flu, but also for checking it. Populations were weakened, and thereby made more susceptible, by shortages and rationing and the fact that many of the strongest and healthiest members had been killed in some trench or no-man’s-land. But the war had also advanced medical learning and germ theory, and steeled people to hardship. They were used to self-sacrifice and putting the nation before the individual. So they were more calm and cooperative with the measures taken by their public health departments, some of which were tremendously restrictive.

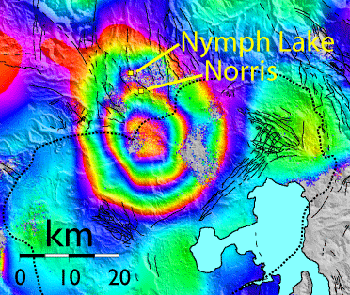

Yellowstone National … Supervolcano?

Yellowstone National … Supervolcano?So what exactly is a supervolcano? Just picture a volcano with 10,000 times the explosive force of Mount St. Helens. And unlike Mount Fuji, supervolcanoes aren’t available in nice cone shapes. Rather, these extreme volcanoes form in depressions called calderas, where the magma gets so thick that gas can’t escape. The pressure keeps building and building until all hell literally breaks loose.

We have our very own supervolcano under Yellowstone National Park. The entire park. In fact, the caldera under Yellowstone is so big – 4,000 square kilometers – no one knew it was there until satellite images told us so. By all estimates, it erupts about every 600,000 years, and the last eruption was 640,000 years ago. We’re due.

So what happens if it blows? The last eruption of a supervolcano was at Lake Toba in Sumatra 75,000 years ago. So much ash was released into the atmosphere that the sun was blocked out, the global temperature dropped 21 degrees, and three-quarters of all plant life in the Northern Hemisphere died. Ice age, anyone? Hopeful geologists content that we may be saved by the venting that occurs at Yellowstone through geysers like Old Faithful, relieving a bit of pressure from the caldera. Let’s hope they’re right.

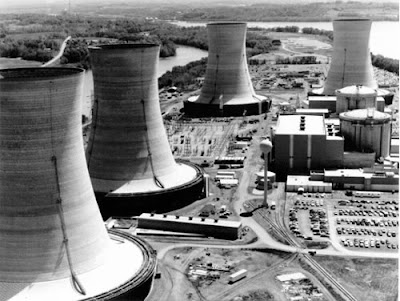

Better Disasters through Science: The China Syndrome

Better Disasters through Science: The China SyndromeOK, so it’s not technically a purely natural disaster. But it involves a lot of physics and stuff, and it would certainly cause one heck of a natural disaster.

The name (from the film The China Syndrome of 1979, the same year as the Three Mile Island snafu) comes down from the theory that, in the event of a meltdown, molten nuclear material would be so hot that it would melt all the way through the earth and come out in China. Of course, we all know that’s just plain silly.

But experts do tell us that a melting reactor core would be able to sink about 15 meters into the earth’s crust, at which point it would hit the water table. The resulting massive release of hot steam would then throw the material back out of the earth with tremendous force, causing the radioactive fallout to be spread across an even wider area. Feel any better about it? We certainly don’t.